Furniture

Cabriolet chair

-

Cabriolet Chair

Paris, circa 1780

Sculpted and painted beechwood

Aglaé de La Blanchetai bequest, 1993

Inv. 989 549 A© Photo MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance

-

Cabriolet chair. With an oval-shaped back

Paris, circa 1780

Sculpted and gilt beechwood

Paul Cosson bequest, 1926

Inv. 25194© Photo MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance

The cabriolet chair has a more or less curved back, as opposed to the flat-backed à la reine chair or side chair. The cabriolet chair was placed in the middle of the room and the à la reine chair against the walls. The term cabriolet designates a chair whose back is curved for greater comfort.

The novel features of this chair by an anonymous maker are its ornate decoration and the shape of the back, midway between square and oval. Although made compulsory by decree by the Parlement de Paris in 1637, stamping furniture with the maker’s mark did not become widespread until the 18th century, but it was still not systematic.

Armchair à châssis

In the wealthiest residences, the upholstery of so-called “tapisserie” chairs was changed twice a year, for greater comfort but also for aesthetic reasons: warm, winter fabrics such as velvet were changed for lighter fabrics such as taffeta in summer. The joiner adapted the chair’s structure to facilitate this, mounting the upholstery of the seat, back and armrests on removable chassis or frames. Servants kept the out-of-season upholstery components in the house’s storeroom. The term cabriolet designates a chair whose back is curved for greater comfort.

Paris, circa 1775

Sculpted and gilt beechwood

Purchase, 1890

Inv. 5613

Armchair à la reine

This armchair’s straight, tapering, fluted legs and medallion-shaped back are characteristic of the Louis XVI style. Its decoration shows the adoption of the neoclassical ornamental vocabulary: the seat rim is sculpted with a frieze of tracery surmounting a frieze of chevrons alternating with beading. On the top of the back, the Louis XV scallop motif has been replaced by a bouquet of flowers framed with laurel branches. Although not rivalling Georges Jacob and Jean-Baptiste-Claude Sené’s extraordinary creations for the court and particularly for Queen Marie-Antoinette, this armchair illustrates the degree of excellence attained by chair makers in the last third of the 18th century.

-

Armchair à la reine with oval-shaped back

Claude-Étienne Michard (1732-1794), master in 1757

Paris, circa 1775-1780

Sculpted and gilt beechwood

Purchase, 1887

Inv. 3492© Photo MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance

-

Armchair à la reine

Jean-Baptiste-Claude Sené (1748-1803), master in Paris in 1769

Paris, circa 1770-1780

Sculpted and gilt beechwood

Loaned by the Mobilier national, 1927

Inv. MOB NAT GME 1549© Photo MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance

Like all the chairs in this room, this armchair is ornately sculpted, indicating that it was made for the drawing room or study of an aristocratic home or royal residence. Sené worked for the royal palaces at Versailles, Saint-Cloud and Fontainebleau, and was among those who did most to propagate the notion of a return to classical sources. The motifs he sculpted in wood are borrowed from architecture: beading, foliation, acanthae, heart-shaped leaf-and-dart moulding, etc.

Harp

Music was one of the main pastimes and entertainments in aristocratic drawing rooms. The harp became especially popular following Marie-Antoinette’s arrival at the French court. A very accomplished player, as dauphine then queen she set an example for the practice of this instrument particularly suited for romantic music. In the 1770s Paris became renowned for its harp makers. Blue, green or black Martin varnish, imitating Asian lacquers, was frequently used for the body’s uniform decoration and to embellish the soundboard with delicate bouquets, foliation and volutes. The other parts of the instrument were in sculpted and gilt wood.

-

Blue harp

Sébastien Renault (died after 1804) and François Chatelain (died after 1800), makers

Paris, circa 1785

maple body, Martin varnish decoration, pine soundboard, crochet mechanism, 7 pedals

marked on the console : SB RENAULT / ET CHATELAIN / A PARIS

Gift of David David-Weill, 1922

Inv. 22359© Photo MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance

-

Harp with the blazon of France

Jean Louvet (mentioned in 1791), stringed instrument-maker

Paris, circa 1780

Natural polished wood and sculpted and gilt wood

Gift of Monsieur Lion, 1906

Inv. 13018© Photo MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance

Chest of drawers

ROGER VANDERCRUSE, known as LACROIX, RVLC, was one of the great names of French cabinetmaking in the second half of the 18th century. He was particularly renowned for his small tables decorated with intricate marquetry and inlaid with porcelain plaques. The characteristic curves of the Louis XV style have disappeared, replaced by architectural lines emphasised by the use of bloodwood, whose parallel veins and contrasting colours provide a decorative motif in their own right. Cabinetmakers demonstrated their talent in their art of combining both indigenous and tropical hardwoods in function of their colour and appearance.

Paris, circa 1780

Bloodwood veneer, gilt bronze, Brocatelle Violette d’Espagne marble

Donation in memory of Monsieur Émile Perrin, member of the Institut de France, a tribute from his son Émile, 1909

Inv. 16393

Roll-top desk

In all likelihood, it was the cabinetmaker Jean-François Oeben who invented the roll-top desk, to cater for the need to both store documents and conceal work from view. It represents a form of evolution from the flat-topped desk towards the secrétaire writing desk. One could now instantly conceal private papers or work in progress simply by pulling down the roll top and locking it. The work surfaces can be increased with drop-leaf flaps on either side and at the back, enabling four people to work at the same time.

As on a flat writing desk, the drawers are placed symmetrically on either side: two drawers on the left and two false drawers on the right concealing a single compartment in which one could place a safe to keep one’s most valuable possessions.

Oak and pine structure, bloodwood veneer, blue Turquin marble, gilt bronzeg

Donation in memory of Monsieur Émile Perrin, member of the Institut de France, a tribute from his son Émile, 1909

Inv. 16391

Table à toutes fins (all-purpose table)

This all-purpose table is an example of the new category of relatively light furniture which appeared and rapidly became popular during Louis XV’s reign, partly due to the relaxing of etiquette wished by the king himself. These pieces of furniture with varied forms and uses were a response to the dictates of a new sociability, combined with a need for intimacy and desire for a less systematic presence of servants at gatherings of family and friends. The marquetry decoration evokes the English-style gardens dear to Marie-Antoinette, such as those at the Petit Trianon, designed by Richard Mique in the late 1770s.

Macassar ebony, rosewood, amaranth, box, maple, acacia, pear, kingwood

Xavier Houppe bequest, 1924

Inv. 23964

Pedestal table

According to the definition of the pedestal table in the Encyclopédie, “its convenience is to be transported where one wishes.” This pedestal table is mounted on castors and at different times of day can be used as a tea table, writing table or for placing a candelabrum.

Paris, circa 1790-1800

Oak structure painted with red ochre, poplar legs, mahogany veneer, gilt bronze, varnished brass, Brocatelle marble top

Eugène Barriol bequest, 1938

Inv. 33860

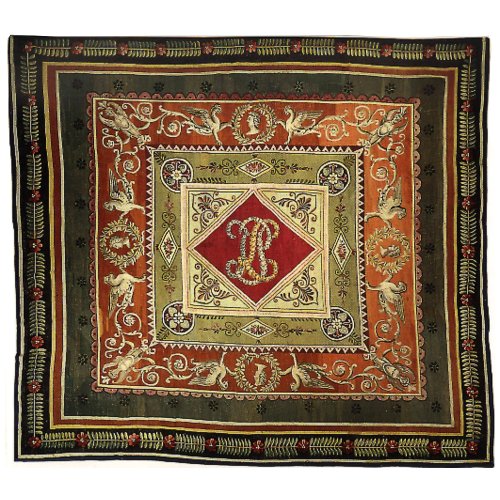

Carpet

This is a rare example of the tapis ras, a type of tapestry-woven or flat-weave carpet that appeared in the 1770-1780s, produced by the Savonnerie manufactory, so-named because it was located on the site of a soap factory on the Colline de Chaillot in Paris. Due to growing demand, other manufactories were soon authorised to weave them.

The Aubusson manufactory, which employed a host of privately-owned workshops under royal control, began producing tapis ras in 1743. These carpets’ compositions often reproduced the decoration on the ceiling and the geometrical division of the room space. The motifs - foliation, medallions, cameos, griffons and chimera - show the contemporary interest in antiquity. The colours - Pompeii red, almond green, deep brown - are a manifestation of the emerging fashion that would triumph during the Directoire and the Consulat, promoted by Dugourc and Bélanger and subsequently disseminated by Percier and Fontaine.