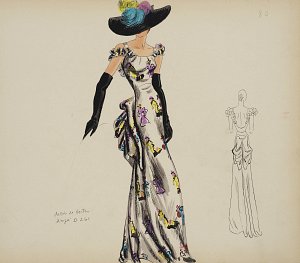

The 6,387 drawings of collection

Elsa Schiaparelli, Collection drawing, Summer 1939

Drawing. Musée des Arts décoratifs

© Les Arts Décoratifs

The donation made by Elsa Schiaparelli

to the UFAC in 1973 included 6,387

collection sketches dated from 1933

to 1953 and compiled in 55 bound and

loose-leaf albums. These unsigned

drawings were made in graphite, coloured

pencil, ink, felt-tipped pen, watercolour

or gouache on drawing paper. Following

the presentation of a collection in the

salons of the maison de couture, artists,

employed by the Maison Schiaparelli,

would rapidly and carefully reproduce the

silhouette of a model wearing the design.

[…] Unlike drawings signed by illustrators

in fashion magazines, these drawings

were never intended to be published.

Along with the programme that indicated

the theme and trends of the collection

and was distributed to those invited

to see the collection, the drawings were

intended as tools to convey technical

information and promote the collection

to clients unable to see the collection

in person, allowing them to place orders

from a distance. […]

The collection drawings constitute a living

memory of the numerous pieces created

by Schiaparelli over twenty years and four

annual collections: Spring, Summer, Fall

and Winter. They show the rich variations

in a collection and the ever-active

power of seduction of Elsa Schiaparelli’s

creations.

Costume Jewellery

Alberto Giacometti, Button 1937

Golden bronze. Musée des Arts décoratifs

© Les Arts Décoratifs

The Schiaparelli silhouette was composed

of clothing, accessories – hat and

gloves – and jewellery, made by master

jewellers, that lent a harmonious and

ornamental touch to the ensemble. Called

“paruriers,” these makers of costume

jewellery worked in the background and

never signed their contributions. The

theme of each collection was transmitted

to the artisans, who then proposed

jewellery in the same spirit. Schiaparelli

surrounded herself with people who

had strong personalities, capable

of understanding her fantastical vision

and also surprise her. Jean Schlumberger

interpreted with elegance the Surrealist

spirit of the couturière. The jewels

of artists Alberto Giacometti and Meret

Oppenheim were equally surprising. In her

memoirs, Schiaparelli spoke glowingly

about other collaborators: faithful Jean

Clément “a genius at what he did,” Elsa

Triolet, the wife of poet Louis Aragon, who

created necklaces in the form of aspirin

tablets, and silversmith François Hugo, the

great-nephew of Victor Hugo, who made

buttons for the designer.

Jean Cocteau, A Poetic Line

Elsa Schiaparelli, Evening Coat, Fall 1937

Rayon knit, Silk embroidery and flowers by Lesage

© Philadelphia Museum of Art

As proof of their friendship, poet Jean

Cocteau offered two drawings to Elsa

Schiaparelli, whom he considered

to be “the most eccentric of designers.”

The couturière transferred the drawings

to an evening coat and a suit jacket in the

Fall 1937 collection. The continuous line

of the drawing embroidered onto the back

of the coat gave the illusion of a double

image: that of two faces in profile looking

at each other, and that of a vase sitting on

a fluted column, crowned by a bouquet

of roses. The collaboration, which exalted

poetic imagination, was also evident

on the evening jacket in the form of a line

that traced the contours of a feminine face

with long golden hair embroidered down

the sleeve. The name Jean punctuated

with a star was Cocteau’s monogram.

In her memoirs, Schiaparelli calls his film

Blood of a Poet (1930) Surrealist, though

he always refused the label. According

to the artist, he was attempting to imitate

a waking dream, which allows one, like

magic, to pass through to the other side

of the mirror.

The Butterfly and its Metamorphosis

Elsa Schiaparelli chose a theme for each

of her collections. For Summer 1937

it was the butterfly. According to the

presentation in the show’s programme, the

collection’s summer prints were intended

to evoke a dance in which singing birds,

buzzing bees and joyful butterflies all

united in harmony. For the designer,

as for the Surrealists, the butterfly was

a source of marvel and aesthetic emotion.

Because they are born from an egg,

transformed into caterpillars and then ugly

chrysalids, butterflies were considered to

be a symbol of the fragility of beauty and

the brevity of life. The beautiful insect,

with its fluid movements and velvety

wings, always flying just out of grasp, was

compared, like a fairy tale, to women and

their inconstant hearts. The butterfly is

at the origin of Apuleius’ 2nd Century story

of the beautiful Psyche (a Greek word

that means both soul and moth) who falls

under the spell of a monstrous god.

Meret Oppenheim, Surrealist Artist

Swiss – German by birth, artist Meret

Oppenheim arrived in Paris in 1932 where

she became close to André Breton,

head of the Surrealist movement, and

photographer Man Ray. In the spring

of 1936, she sold Elsa Schiaparelli

a design for a piece of jewellery:

a brass bracelet covered in animal fur

that Schiaparelli included in her Winter

1936 – 37 collection. Meret wore the

bracelet at the Café de Flore in the

company of Pablo Picasso and Dora

Maar, who admired it. Over the course

of their conversation, a project was born

to cover every object on the table in fur.

Their tea having gone cold, they ordered

a “bit more fur” from the waiter! Invited

by Breton the following May to participate

in an exhibition of Surrealist objects at

the Galerie Charles Ratton, Oppenheim

presented Le Déjeuner en fourrure

(Lunch in Fur): a teacup, saucer, and

spoon, covered in fur. This surrealist

set of objects was bought by Alfred H.

Barr for the collections of the Museum

of Modern Art in New York.

Leonor Fini, The Triumphant Femininity

of Shocking Perfume

Born in Buenos Aires of Italian origin

(from Trieste), Leonor Fini arrived

in Paris in 1931. Presented to Christian

Dior by Max Jacob, she showed her

paintings in the Galerie Bonjean directed

by Dior. Schiaparelli discovered her

fantastical creative universe peopled with

mythological feminine figures. In 1936 she

painted the portrait of Gogo Schiaparelli,

Elsa’s daughter. At the couturière’s

request, Fini designed the Shocking

perfume bottle.

Place Vendôme

François Kollar, Madame Schiaparelli, 1938

Photograph

© RMN – Gestion droit d’auteur François Kollar, Charenton-le- Pont, Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie © Ministère de la Culture - Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / François Kollar

By the mid-1930s, Elsa Schiaparelli

had come to the forefront as a premier

couturière. In 1933, she opened

a boutique in London and in January 1935

she moved out of her shop at 4, Rue

de la Paix, which had become too small.

She chose to open her new Paris shop

in a mansion at 21, Place Vendôme, whose

façade dated from the 17th Century. […]

On the ground floor of the building, was

the Boutique Schiap which sold, “prêt-àporter:”

evening sweaters, skirts, blouses

and accessories. She called on Jean-

Michel Frank for the interior design of the

three principal salons de couture whose

Louis XV woodwork was painted white.

For Frank, elegance meant eliminating

things to attain simplicity. He worked

with Alberto Giacometti to design the

rare decorative elements, like the plaster

columns topped with shells that housed

lighting. Dramatically draped curtains

lent a theatrical touch to presentations

of the collections by models in the

streamlined, monochrome rooms.

Light played a fundamental role in shaping

the space and contributed to creating

a surreal and strange atmosphere, in the

manner of a Dalí landscape. The central

presence of the Vendôme column is felt

in a collage given by Marcel Vertès

to Schiaparelli in 1953, the year before

the company closed. A veritable resumé

of the designer’s most emblematic

pieces, the work, by the artist

of Hungarian origin, was a vibrant homage

to Schiaparelli’s inventions.

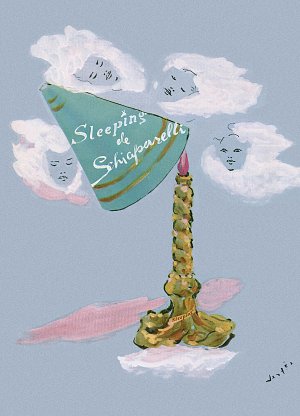

The Perfume Cage

Marcel Vertès, Advertisement for the Schiaparelli perfume Sleeping, 1945

© Archives Schiaparelli

In February 1934, Elsa Schiaparelli,

superstitious, launched three perfumes:

Soucis, Salut and Schiap, all three

of which began with the letter ‘S’.

The trapezoidal bottle for Salut and its

cork box were designed by Jean-Michel

Frank. In June of 1935, on the ground

floor of the maison de couture, a perfume

cage imagined by Frank was installed.

Its structure, in golden bamboo and

black metal, allowed for a spectacular

presentation of perfume and cosmetics.

The Boutique Schiap raised the curiosity

of tourists to meet the wooden couple

holding court: Pascal “the permanently

Greek beauty” and his faithful Pascaline.

In April 1935, the perfume Shocking, with

its bottle designed by artist Leonor Fini,

became the successful signature of the

house. In January 1947, the Parfums

Schiaparelli group moved to a modern

laboratory in Bois-Colombes where the

perfume Le Roy Soleil, with its Baccarat

crystal bottle designed by surrealist

artist Dalí, was produced in a very

limited edition.

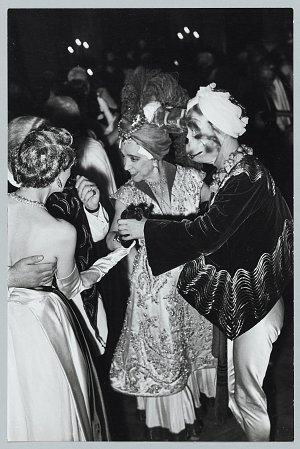

The Commedia dell’Arte

Nepo Arik, Elsa Schiaparelli dansing with a man wearing a Schiaparelli jacket at a Fath Ball at Corbeille, 1952

© Elsa Schiaparelli SAS © Droits réservés, Paris, Palais Galliera - Musée de la mode © Paris Musées, Palais Galliera, Dist. RMNGrand Palais / image ville de Paris

The theme of Commedia dell’Arte

defined the Spring 1939 collection. This

form of comic theatre originated in the

popular Italian culture of the 16th Century.

The plays were performed by masked

characters, identifiable by their familiar

costumes, speaking improvised dialogues

that made the public laugh and react

out loud. Arlequin’s costume, a diamond

mosaic, was reinterpreted with elegance

by Schiaparelli in a series of evening

coats. A great lover of the sumptuous

masked balls and costume parties

organized by her clients, Schiaparelli

developed in this collection her taste

for amusing disguises. Her theatrical

references were shared by painter André

Derain who painted Arlequin and Pierrot

with great melancholy. The title of the

collection, likely intended to be ironic,

echoed the worrisome comedy being

played out on Europe’s stage that year

following the Munich accords that had

been signed in September 1938.

The Signs of the Zodiac

Salvador Dalí and Baccarat, Perfume Bottle Le Roy Soleil, 1946

Crystal

© Archives Schiaparelli

Observing Elsa Schiaparelli’s face, her

astronomer uncle Giovanni Schiaparelli

compared the beauty spots on her left

cheek to the seven stars in the Big Dipper

constellation. She made it her personal

trademark and often decorated her

creations with it, along with other celestial

motifs. The Winter 1938 – 39 collection

shone with signs of the Zodiac, planets

and constellations. The theme was fleshed

out with references to the reigns of Louis

XIV and Louis XV, the château, and

gardens of Versailles where, harmonious

connections between the seasons and

the planets were represented throughout

the interior and exterior design. A cape

was embroidered with Phoebus,

a reference to the Sun King, while the

Manufacture de Sèvres, created by Louis

the 15th, inspired the decoration of a coat.

A jacket covered in fragments of mirrors

in baroque-style golden frames, was

perhaps inspired by the doors in the

Versailles Salons of War and of Peace.

Circus

Elsa Schiaparelli, Boléro Cirque, Été 1938

Broderie de ganse

de soie sur crêpe de soie,

broderie de fils de soie,

lacets, cabochons, perles

et miroirs par Lesage.

Musée des Arts décoratifs

© Les Arts Décoratifs / Christophe Dellière

The Summer 1938 collection was built

around a circus theme. Its presentation,

the 4th of February 1938 in the private

salons at Place Vendôme, took the form

of a burlesque show that enchanted

those present. Elsa Schiaparelli wrote

in her memoirs that it was the most

“tumultuous, most audacious, collection”

where clowns were let loose in a crazy

dance. Elephants, trapeze artists and

horses decorated the bolero evening

jackets. Composed of 132 pieces, the

inventive and joyous collection combined

references to the circus with the Surrealist

movement. And indeed, the collection’s

show coincided with the International

Surrealism Exhibition, organized in Paris

by André Breton and Paul Eluard, in which

artists Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Pierre

Roy and Salvador Dalí, among others,

participated. The human-skeleton circus

number was at the outset a bony skeleton

embroidered on an evening gown, inspired

by a Dalí drawing.

The art of Embroidery

In 1934, Elsa Schiaparelli asked Albert

Lesage, head of an embroidery studio,

to work on several embroidered belts.

The collaboration went well and from

1936 on she turned to him to add handembroidered

decoration to her creations,

illustrating the themes of her collections.

Highly regarded for his creative talent and

his savoir-faire, Albert Lesage’s embroidery

was faithful to Schiaparelli’s inventiveness

and her fine sense of humour. It was

a stimulating exchange: an embroidery

sample could end up influencing the

design of a dress. For a collaboration with

Cocteau in 1937, Lesage embroidered

the poet’s drawings, in particular that

of a magnificent woman with golden

hair, on a linen jacket. The Lesage

studio also fabricated the little bouquets

of flowers that decorate the Shocking

perfume bottle. In 1949, François Lesage

succeeded his father and pursued the

studio’s collaboration with Schiaparelli

until 1954.

-

Elsa Schiaparelli, Bolero Circus, Summer 1938

Silk embroidery, laces,

tiles, pearls and mirrors by Lesage. Musée des Arts décoratifs

© Valérie Belin

-

Daniel Roseberry, Look 10, Spring-Summer 2022

Photograph

© Maison Schiaparelli