Born at Lwów, Roman Cieslewicz completed his artistic training at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, graduating in 1955. He became a major figure of the Polish Poster School, the artists who revitalized the medium and its role in the 1950s, and whose fame and influence spread internationally. But the complex political context and his ambition to expose his talents to the “neons of the West” are two of the reasons why Roman Cieslewicz chose to leave Poland.

He arrived in Paris in 1963. Hired by Peter Knapp as a layout artist, he contributed to Elle magazine and became its artistic director. In 1967, he took part in the creation of a new art magazine, Opus International, defining its graphic image. He also worked for Vogue, the publishing house 10/18 and Jacques-Louis Delpal.

He was the first artistic director of the MAFIA agency.

Although he soon abandoned the visual aesthetics and techniques he used in Poland to explore photomontage, he kept the idea that the role of the poster and graphic design is to educate the public both intellectually and aesthetically and “depollute the eye.”

Alongside his commissions, he continued what he called his “studio” production, largely consisting of series of collages and photomontages, creating the “repetitive collages” and “centered collages” that led to other remarkable series such as Change of Climate and No News is Good News. A member of the Panique group, founded in 1960 by Arrabal, Topor, Jodorowski and Olivier O. Olivier, Cieslewicz created Kamikaze, Panique’s news review, in 1976.

Roman Cieslewicz had his first major exhibition in France at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in 1972. In 1993, the Centre Georges Pompidou paid tribute with a comprehensive retrospective, followed by the Musée de Grenoble in 2001. Although major museums have already celebrated his work, the exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs analyses Roman Cieslewicz’s creative process by showing documents from his archives for the first time and approaching it in an innovative manner. Taking us on a chronological journey through his work and focusing on themes dear to Cieslewicz such as the eye, the hand, the circle, Che Guevara, the Mona Lisa, it reveals the workings of Cieslewicz’s “image factory.” His works dialogue with his iconographic archives, kept at the IMEC (Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine), some of which are being shown for the first time.

Roman Cieslewicz, Il est exactement 1989 Non stop, série Kamikaze 2, revue d’information Panique magazine, 1991

Double-page layout

© Adagp, Paris 2018 Photo : Paris, MAD Jean Tholance

From room to room, we are plunged into the rich world of Cieslewicz’s’s graphic creation, evoked by posters, advertisements, magazine covers, videos and a recreation of his studio giving us an intimate and passionate insight into the artist’s image-making processes.

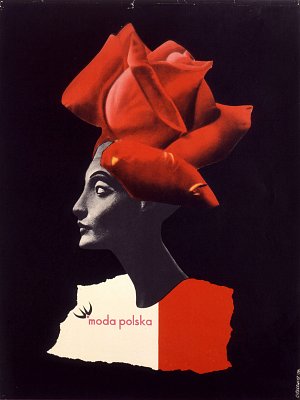

Roman Cieslewicz, Moda Polska, 1959

Poster. Zurich, Museum für Gestaltung

Photograph courtesy of the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Poster Collection, ZHdK © Adagp, Paris 2018 Photo : DR

He read the newspapers everyday, classifying his cuttings in more than 350 boxes covering a huge variety of themes. Roman Cieslewicz’s archives were the raw material he used to create and mirrored the man he was. They reveal his key preoccupations, artistic influences (Dada, the Russian avant-garde, Bruno Schultz) and his friendships (Topor, Arrabal, Depardon, etc). They are also a man’s vision of his time: by using media and advertising imagery, the celebrities of the period and artistic icons to comment on contemporary events, he developed a critical view of the world and revealed another truth.

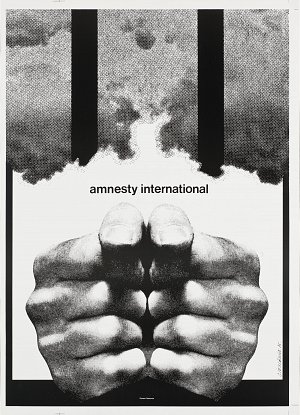

Roman Cieslewicz, Amnesty International, 1975

Poster

© Adagp, Paris 2018. Photo : Paris, MAD / Jean Tholance

The exhibition’s comprehensive catalogue plunges us into the artist’s daily work process. In the form of an alphabet book, it features texts by contemporaries who knew Roman Cieslewicz and is abundantly illustrated with images from the artist’s own archives.

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs, which has one of the richest and oldest graphic design collections in France, is delighted to be again paying tribute to Roman Cieslewicz with this ambitious and comprehensive retrospective.