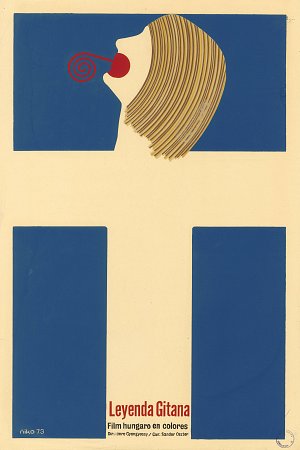

Niko (a.k.a. Antonio Perez Gonzales), Leyenda gitana

Dir: Imre Gyongyossy

© MAD, Paris

While posters started appearing on the island from the late 19th century, it was not until the revolution that poster design became a more elaborate artistic practice. Until 1959, posters were primarily commercial, encouraging the consumption of imported products and following the aesthetic example set by American advertising. At the Revolution’s close in 1959, Che Guevara – appointed Minister of Industry – banned commercial advertising and posters consequently started reflecting the politics and culture of the era.

Cuban political posters found their inspiration in the historic events of the Revolution and feature its heroic figures, with subjects such as: Fidel Castro’s first attempt to overthrow General Fulgencio Batista with the attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba in 1953; the establishment of the revolutionary “26 July Movement”; the comrades in arms of the Guerrilla campaign with the figures of Che and Camilo Cienfuegos; the capture of Havana and power by the Guerrilla forces in 1959; and the invasion of the Bay of Pigs by the United States in reaction to Cuba’s strengthening ties with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

-

Dimas (a.k.a. Jorge Dimas Gonzales Linares)

ICAIC, 1973

© MAD, Paris

-

Olivio Martinez, October 8: Day of the Heroic Guerrilla OSPAAAL

OSPAAAL, 1973

© MAD, Paris / photo: Christophe Dellière

The Organisation of Solidarity of the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL) and the Department of Revolutionary Orientation (DOR) were the two main organisations publishing political posters during this period. OSPAAAL was in charge of issues concerning international solidarity – in particular with the developing world – and DOR dealt with the country’s revolutionary orientation. Felix Beltran and Alfredo Rostgaard’s beguiling work epitomizes the posters printed by both governmental agencies.

Cultural posters, on the other hand, were almost exclusively linked to cinema, an industry that played an integral part in Cuba’s history. In 1943, there were 422

movie theatres across the country. Fidel Castro designated film the “seventh art,” claiming it as one of the principle tools for educating the people and implementing

his cultural policies.

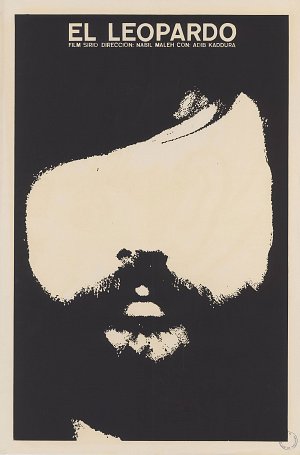

René Azcuy Cardenas, El Leopardo film sirio

ICAIC

© MAD, Paris

From the time of its creation in 1959, the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) became the most important source of poster commissions. It quickly imposed novel styles that favoured the Cuban poster

design exemplified by key figures such as René Azcuy Cardenas, Niko, Eduardo

Munoz Bachs and Antonio Reboiro, and which garnered the Cuban poster art

international recognition.

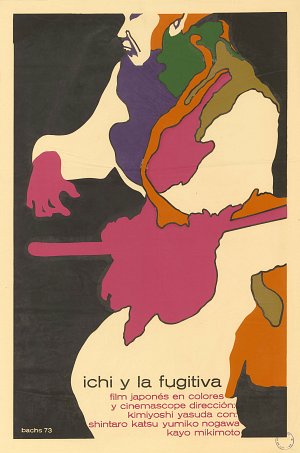

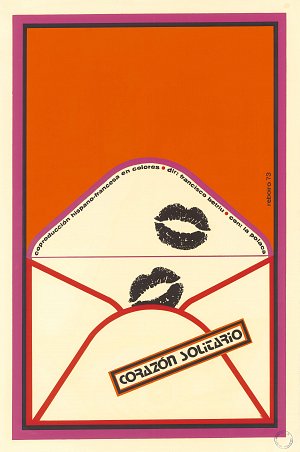

Cuban cinema posters started evading the aesthetic conventions established by local

branches of American communications agencies before the revolution. Rather

than present a portrait of the leading actor or a film still, Cuban poster artists employed free and creative interpretation of the films’ narratives. Considered

an instrument of propaganda after the revolution, it was mandated that posters

educate viewers about art and incite pleasure. Poster artists started drawing inspiration from contemporary art movements including pop, psychedelic,

and kinetic art. Unlike other communist regimes that mandated an adherence to

a social realist aesthetic included in poster design, Fidel Castro advocated total

freedom of form, seeing the poster as a “large-format visual manifestation within

reach of the people who frequent neither museums nor galleries.”

Eduardo Munoz Bachs, Ichi y la fugitiva

Direccion: Kimiyoshi Yasuda, ICAIC, 1973

© MAD, Paris

Cuban posters were highly sought-after until policies implemented in the mid 1980‘s brought forth events that would lead to the eventual fall of the Soviet Bloc and with it 80% of the export trade on which Cuba relied. Cuba entered a deep economic crisis and poster production came to an abrupt halt. Young graduates of the Instituto Superior de Diseño (ISDi) consequently began their careers within a context of significantly reduced public commissions. Designers joined forces

in small, independent groups such as Next Generation (1993-1997), founded

by Pépé Menéndez.

Work created by the collective NUDO, formed by Eduardo Marin and Vladimir Llaguno, demonstrates a provocative rebellion against previously accepted rules of graphic design. The 2000s saw the arrival of a new generation

of Cuban poster designers that would undertake a resolutely experimental artistic

practice.

The exhibition’s chronological and monographic layout introduces viewers to Cuba’s history through the political posters, contextualising the major events that inspired the artists of the revolutionary period.

Antonio Reboiro, Corazon solitario

Dir: Francisco Betriu, ICAIC, 1973

© MAD, Paris

It continues with film posters and an exploration of the ICAIC,

one of the greatest commissions of such work, featuring the designs of major figures such as René Azcuy Cardenas, Niko, Eduardo Munoz Bachs and Antonio Reboiro. Finally, the exhibition explores the new generation of artists, revealing the richness of contemporary production. It includes pieces from the private collection of Luigi Bardellotto, never before seen in France.

Affiches cubaines : révolution et cinéma, 1959-2019 invites visitors to

explore a graphic cultural heritage that

is little known today, resituating it in its

rightful place within the international

history of poster design.